Not houseboats. An apartment complex. Amsterdam permitted this a couple of decades ago, and it was complete by 2011. Prefab houses built on concrete tubs that are half-submerged as ballast, anchored to the bottom. Beautiful, and practical, and a few other cities are starting to think that, with 1m sea-level-rise, they should start looking at how to add flexible housing like this.

Monthly Archives: February 2022

Heather Cox Richardson is Tom Paine

I think she is playing the role that Tom Paine played. Explaining what’s what for the common man.

George Crumb died

Oh. I’m getting to that age, where all the people I used to look up to are disappearing.

The Guardian and Music

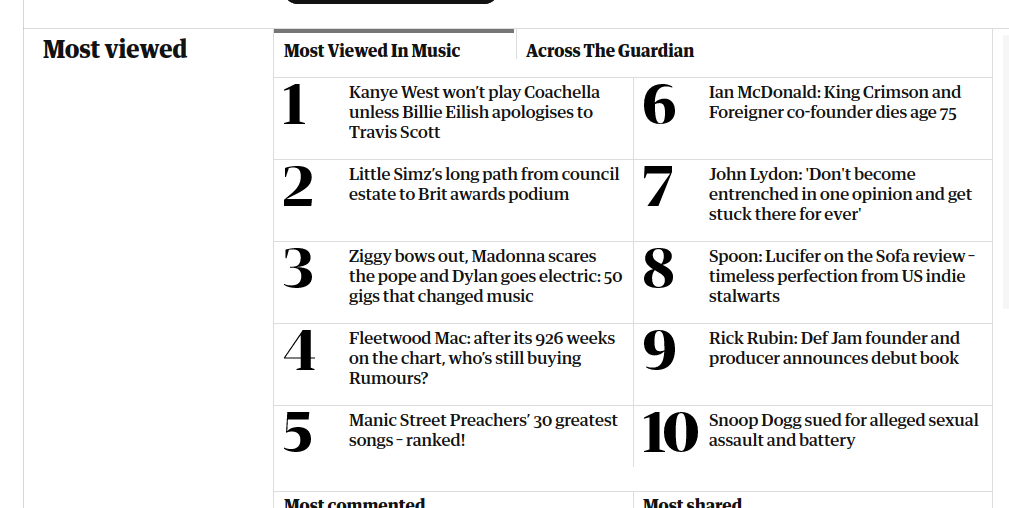

Screenshot of the top 10 Music stories on the Guardian website today:

King Crimson, John Lydon, Madonna, Dylan, Fleetwood Mac, Def Jam, Snoop Dogg … wow. Music hasn’t moved on much since I was a kid.

Jon Appleton, composer and Synclavier innovator, has died – CDM Create Digital Music

https://cdm.link/2022/02/jon-appleton-composer-and-synclavier-innovator-has-died/

When I was running sound at the U of Auckland, they held a conference and Jon Appleton presented the Synclavier. He came to me before he gave the paper and asked that I make available four channels of audio input, set the levels once, and then leave the board alone. Intrigued, I attended the presentation.

I was completely blown away. I’d dabbled in analog electronics for audio since high school, but this presentation set me on a course of working with computers to make music.

I got in touch with Appleton when I was in the US, asking about graduate school. He told me not to bother, to just keep working in the field outside of academia. Glad I didn’t listen to him and joined the CCM at Mills instead. Interesting note: Larry Polansky, one of my thesis advisors, ended up running the department at Dartmouth where Appleton taught.

Who’s got the power?

There’s been a rise in the visibility of abuse of power one group to another in the past few years: the #MeToo movement, Black Lives Matter, pushback against trans-phobia, … As these ideas matured, they’ve gone from illuminating injustices that were formerly condoned or invisible to be wielded as weapons against transgressors, often bringing on very public falls from grace. In short, they’ve arrogated power to groups of people who formerly were powerless; by identifying as with a group, the powerless have taken back power. It’s no coincidence that many such groups model their operation on the civil rights movement of the ’50s and ’60s.

This is coincident with another well-documented trend of the last few decades, that of economic inequality (the 10%, the second Gilded Age, etc), and I’ve come to think it’s not an accident. It’s become clear that economic inequality goes hand-in-hand with an imbalance of power; for example, see the Princeton study showing government activity being completely unrelated to what the “regular guy” wants and close correlated with what the wealthy individuals and corporations prefer.

As a result, I believe the general population have become increasingly of the opinion that the institutions and formal processes of society, the law, the government, the police, the media, and so on are not operating in their interests. This ties in with the lack of trust in such institutions that Fukiyama speaks of.

In such a society, how do you move the levers to address issues that are of concern to you? You can’t sue, because the courts aren’t your courts. You can’t appeal to normal democratic institutions, because the government doesn’t have your interest at heart. You can’t expect the media to help, because they don’t tell the truth. In many respects, you’re like the small child in a dictatorial family, not listened to in conversation, powerless.

Children revert to using the power they have: to invoke sympathy, to demand attention. When you’re powerless, you need to get the powerful on board, and you can do that to some degree by invoking shame, anger, or at least making enough noise to make the powerful pay attention to you. I think this is the basis of the rise of the groups I mentioned above. Not to imply that they’re childish, but that they find themselves (as do 90% of us) without access to the mechanisms of power to make change that a healthy society supports, and hence must use the mechanisms they have available.

In a reasonable and fair society, an individual or group that was the victim of a clear injustice would be able to use the courts to get redress, or expect their government to listen and address the issue, or present their case to the media and expect that there would be an investigation into the issue and a public airing of the result. But if you believe the courts only work for those with money, the government long ago ceased to be “of the people, by the people and for the people” and the media have abandoned fact-finding for publishing partisan opinions handed down from the rich and powerful, you don’t have access to those mechanisms. So you use the mechanisms you have at hand: make a loud noise, and try to shame or anger the powerful into allying themselves with you and making change on your behalf. The power of the victim.

This has a couple of problems. In order to be effective, it needs to be consequential. Hence the return of shunning as a punishment, often self-imposed, sometimes unjust. The principles of justice that we’ve evolved over time (innocent until proven guilty, proportionate punishment, malicious intent, …) tend to fall by the way. Secondly, the increase in power invites push-back from other groups using similar methods, or simply refusing to acknowledge shame, guilt and the other tools in the powerless’ arsenal, leading to some truly abhorrent abuses by people refusing to acknowledge the justice in the other’s claims. In short, if nobody trusts the institutions that have been evolved to address conflict between groups of people in society, that conflict will express itself in more primitive ways, and will be cynically used or put down in more primitive ways by those who do wield power.

If we addressed economic inequality in society, I believe we’d see a more just and fair airing of legitimate grievances and a willingness to address them.

Ghazala

Ghazala

— Read on www.anti-theory.com/bio/

Maus

A well-considered rebuttal of critics of the school board in Tennessee who removed Maus from their middle-school curriculum.

Where are the Beatles of software?

My friend in NY laments the lack of a model of cooperation in his software work.

http://scripting.com/2022/02/08/164711.html?title=whereAreTheBeatlesOfSoftware

Hmm. Kernighan and Ritchie?

Housing support

When I was young, I lived in a State house. This is a house that was built 50 years earlier by the NZ government for the purpose of satisfying the need for low-income housing. The houses are solid, if unremarkable, and spread all over the country.

In the 1980’s, the Government offered a bunch of these houses for sale, with first right of refusal going to the occupants. Many people took them up on it, and bought into the housing market for a low cost. Effectively, the Government subsidized the purchase of peoples’ first house. Many of those people are now in the fortunate position of owning a house in one of the most unaffordable markets on the planet.

In the US, there’s an agency constituted to help rental tenants own their first house, too, that was set up under the New Deal, Fanny Mae (FNMA). Their charter was to make available and administer the newly-invented 30-year mortgage, a tool that was created at the time specifically to allow people to buy their first home. Some time later, a sister organization, Freddy Mac (FRMC) was set up by Congress for similar reasons, as a way to support buying a house for regular people.

After the bailout of the finance sector that happened after 2008, Wall Street used a chunk of the money given them by the taxpayer to buy up newly-available houses from people who suddenly couldn’t afford their mortgages. They are running them into the ground for a quick profit.

Today, many of these purchases by Wall Street are financed by Freddy Mac at a below-market rate. So the US government, unlike the NZ government, has chosen to use low-cost loans to subsidize the purchase of homes not by the tenants who need the break, but by finance whose incentive is to badly manage the asset for an immediate profit (hiking fees, rental rates and skimping on maintenance) and flip it on.

Pluralistic article “Wall Street’s landlord business is turning every rental into a slum”

This follows a standard playbook for the US government. A problem for some segment of the population is identified, and legislation passed to fund a solution. Rather than simply distributing those funds to the population, however, a private partnership is entered into whereby companies are asked to do the work, and the funding given to them. Oddly enough, this generally leads to corruption, mismanagement, an enrichment of a few smart enough to get on board, and a failure to fix the problem.

The money distributed for relief of suffering during the pandemic is a good example of both approaches. One program, paying families for the cost of child care while schools were not safe to open, was administered as a direct payment to recipients’ bank accounts, and has been reckoned to be the single factor most responsible for pulling 40% of children across the poverty line. Another program, the PPP “loan” for small business (a grant, if used for its intended purpose of furloughing workers) was administered by the banking system in conjunction with the federal government; at least one bank is now being sued for demanding repayment of loans in violation of the conditions of the program.

The US government has a problem with simply giving money back to people. This is an ideological approach to government support of the population for whose benefit the government exists, based on the idea that people who need help don’t deserve it. In contrast, giving money to business is viewed as legitimate. This is a quite different outlook on the function of government to that of the New Zealand I grew up with.